Canon’s New Patent Shows the Path Toward True VR Glasses

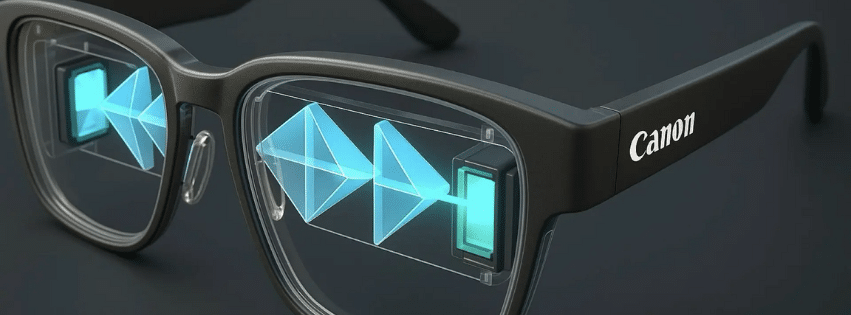

Virtual reality has been held back for years by one stubborn limitation: size. Headsets may deliver dazzling immersion, but their bulk makes them inconvenient for long sessions and far from fashionable for everyday use. Canon’s newest patent of VR Glasses suggests the company is working to solve that problem at the optical level. Instead of chasing incremental refinements, Canon is rethinking how light moves through a headset—aiming to compress a full VR viewing system into something that could pass for ordinary eyeglasses.

A New Approach: Folding Light to Save Space

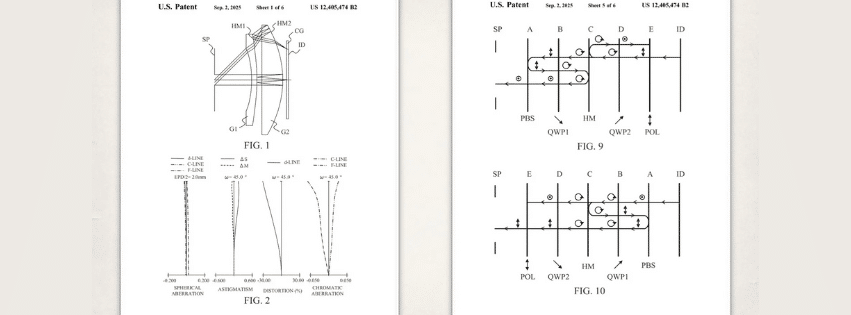

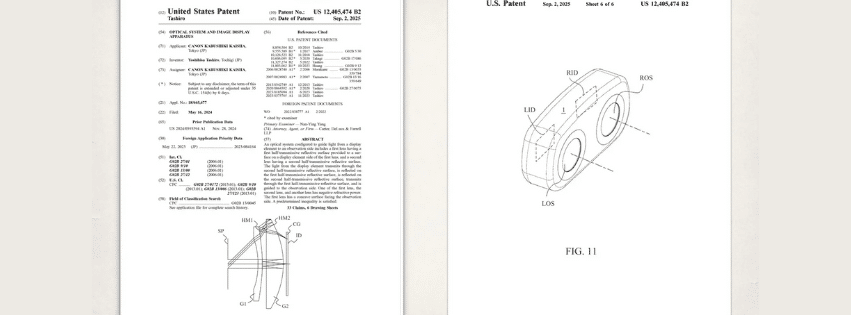

At the core of the patent is a clever optical strategy built around a folded light path. Typical VR headsets rely on thick lenses or long barrel-like structures to bend light from a microdisplay into something the human eye can comfortably view. Canon’s design bypasses those bulky components by making light bounce through the system several times before it reaches the wearer’s eye.

According to the filing, the system uses two half-mirror layers—special surfaces that partially reflect and partially transmit light. These are placed within a stack of lenses. Light from the display enters the first lens, reflects off one half-mirror, transmits through another, and repeats this dance until it travels a full optical path inside a much smaller physical space. In practical terms, Canon is turning the lens itself into a compact light guide, eliminating the long tubes and thick glass slabs that dominate most VR designs today.

This multi-pass system allows the company to maintain a wide field of view. That is critical, because a narrow viewing angle instantly breaks immersion. By routing light efficiently inside the lens, Canon preserves the user’s sense of depth and peripheral awareness—meaning the experience should feel closer to wearing a traditional VR headset, without the headset.

Precision Without the Bulk

Shrinking the optical path alone isn’t enough. Compressing lenses often introduces visual distortions, such as chromatic aberration (color fringing), warping, and soft focus. To compensate, Canon integrates a lens with negative refractive power at a specific point in the path—importantly in a location where the light passes through it only once.

This seemingly small detail matters. Negative-power lenses spread light outward slightly, helping to counteract distortions that would otherwise appear when light bounces around multiple times. Because this lens is used only in one stage of the light path, Canon preserves sharpness without needing thick corrective elements. It’s a surgical level of optical engineering: applying correction exactly where it’s needed, without adding unnecessary weight or volume.

The patent also describes surfaces with concave geometry and specific mathematical relationships that must be met for the system to produce clean, accurate images. While the equations stay behind the scenes, their purpose is simple—deliver clarity while keeping the profile thin.

Moving From Headsets to VR Glasses

When you combine these innovations—a folded light path, half-mirror reflectors, a corrective negative lens, and a slimmed-down frame—a clear picture emerges: Canon wants VR and AR hardware to look like everyday eyewear.

This direction aligns with the broader trend across the industry. Apple has been exploring lightweight mixed-reality concepts beyond the Vision Pro, and Chinese manufacturers like Vivo are racing to release thinner, more stylish head-mounted displays. The industry understands a hard truth: consumers won’t adopt immersive wearables on a mass scale until they resemble something people are already comfortable wearing.

If Canon succeeds, the result wouldn’t just be smaller VR glasses; it would be a shift in how people think about immersive technology. Instead of reserving VR for gaming or professional training, users could incorporate it into normal daily life—navigation, remote instruction, productivity overlays, and beyond.

The Big VR Glasses Picture

Canon’s patent filing points to more than just an inventive lens design. It reflects a strategic push to move immersive hardware from niche to mainstream. By tackling the optical challenges that have kept VR bulky and uncomfortable, Canon is laying groundwork for a major form-factor revolution. Glasses that look and feel like standard eyewear—but deliver a full virtual screen—could dramatically expand who uses VR and how often they use it.

If the future of immersive tech is going to sit lightly on our faces rather than strap tightly to our heads, this kind of engineering may be the breakthrough that finally makes it possible.